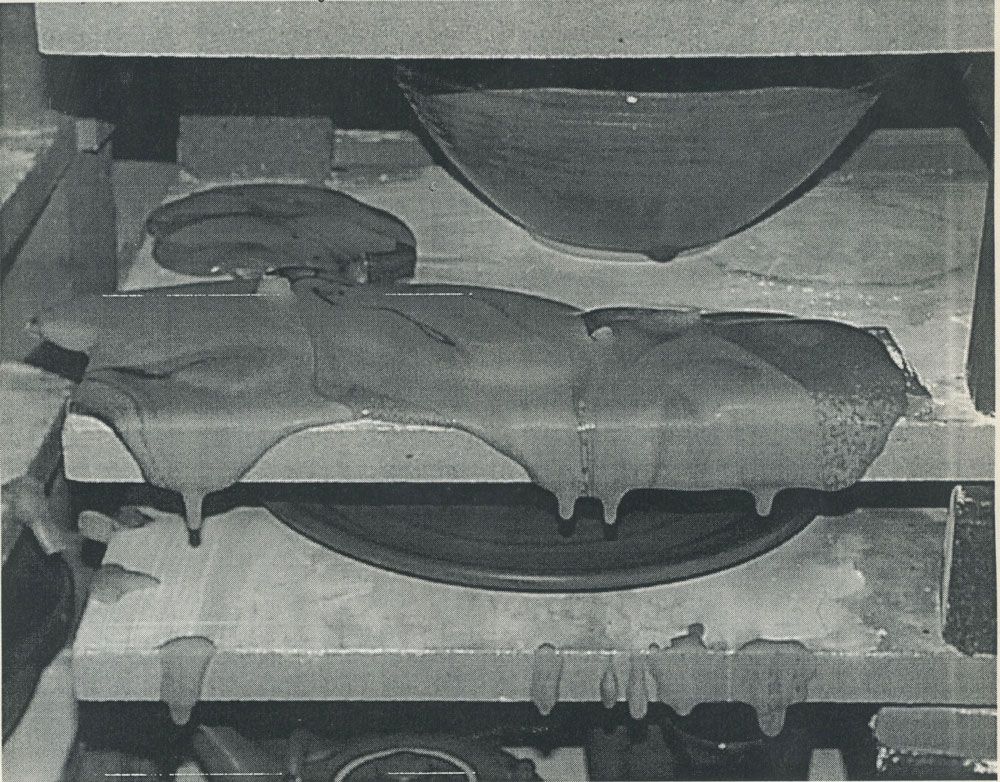

A guy asked me to fire some pots for him and, unknown to either of us, the pots were low-fire Earthenware clay, not Stoneware or Porcelain. The melted stuff dripping off the shelve is all that’s left of his pots. This was a very costly mistake! Thousands of dollars!

Trimming improves the look and feel of you pots, and reduces weight

Even if you can’t “throw thin”, you can at least trim thin.

Make the bottom of your pot smooth, “table frienedly” and interesting.

To control the weight…

1. Throw the pot so it is light and has thin walls. This is difficult and beyond the ability of most beginners, so don’t feel badly if you can’t do this. Beginner can, however, trim off extra weight and extra clay!

2. After throwing the pot, and before you cut it off the bat, take a wooden tool or a metal trim tool and cut away excess clay from the sides of the pot near the bottom. That’s easy. Anyone can do it.

3. When the pot is leather hard, trim it to the proper thickness. We won’t fire overweight pots because they explode.

Are your pots too heavy?

Maybe you should trim off some more clay.

When throwing, trim off extra clay on the bottom half of your pots BEFORE you cut them off the bat.

When your pots are leather hard, trim off a bunch more clay.

Trim until they feel good. I would rather you occasionally accidentally trimmed a hole in your pots rather than leave them too thick. Practice and you will learn.

These two videos will help you trim better

Timing, trimming and Attachments

We dry your pots to leather hard the best we can, but they wont necessarily be perfect. So, first thing when you walk in the studio, check you pots and see what condition they are in. They may be too wet, or too dry. This is a tricky judgement call, but it is a matter of life and death for your pots. So get help and get it right. They may need to dry out for a bit under a fan, or they may need the lip dunked in water. Learn to figure it out.

Handles and other attachments wont stick if your pot is too dry. Pots need to be wiggly at the lip for handles to stick on. Bowls can be a bit dryer at the lip. Structure your time around the needs of your pots.

You can help us to dry your pots evenly if you make them uniform in thickness. So, I repeat, when throwing, trim off extra clay on the bottom half of your pots BEFORE you cut them off the bat.

Glaze can make your pots beautiful

Glazing has an aesthetic side and a mechanical, physical side. First, let me draw attention to the actual act of glaze application and its implications. The way you apply the glaze determines how it will look. You could ruin your pot, or make it spectacular. Good glaze application techniques are critical to your success.

Glazes, in their liquid state, in the buckets, are a mixture of minerals and water. However, when they are fired, those minerals in the glaze will melt and form a glassy coating that fuses to the clay. Further more, the porcelain clay, at maximum temperature, is so hot that the clay becomes as soft as it was on the wheel. So pots can actually slump and collapse if not made properly. Then the clay and glaze fuse.

This glaze melting and fusing takes place as the kiln approaches the maximum temperature. The melting glaze (glass) behaves like honey. The hotter it gets, the more fluid the glaze becomes, just like honey does when you heat it in a microwave. Sticky, thick honey can become as thin as water when heated. The word “viscosity” refers to a liquid’s fluidity. Water has low viscosity and is fluid at room temperature. Honey has a high viscosity and is thick at room temperature. Glaze and glass, like honey, tar, and molasses, when heated become less viscous and more fluid.

In addition to becoming more fluid, glazes also go through a boiling phase, which essentially stirs up the ingredients, causing mottling and mixing of colors. Chun and Oil Spot show these mottling effects.

After the heating cycle (18 hours), when the pots cool, they get hard and rigid again, as do the glazes. At certain points in the cooling, crystals may form in some glazes. Plum and Tomato Red are examples of glazes that have crystals in them. This is also where glaze fit becomes an issue, causing some glazes to crackle.

As mentioned before, good glaze application techniques are critical to your success. You need to use the right glazes on different parts of you pots, and get them the correct thickness. Poor glaze application can cause the glaze to run off the pot in the firing. Here’s how:

- The thicker the coat of glaze, the more likely it is to run.

- Glaze overlaps are always more fluid. This is due to chemical reactions called eutectics, and also because two layers of glaze are thicker than one.

- Some glazes are inherently more fluid than others. Copper Red and Oil Spot always become runny in the firing. Plum is an example of a not very fluid glaze.

The above three things need to be taken into account when you apply glaze. You will be shown in class how to apply glaze. Not all glazes are applied the same. The color of overlaps is not what you would expect with colored paint. Some glazes are easy to use. Some are difficult. If you understand the above information the instructions you receive in class will make sense to you. If not, it will seem like a jumble of arbitrary rules and be quickly forgotten. So think about the above. Ask questions in class or do some research, and be prepared to LEARN PROPER GLAZE TECHNIQUES in class.

Fireborn glazes are incredibly beautiful, so if you learn proper techniques, you can make even a humble pot into a thing of beauty.

Videos about Glazing

Glazing can also ruin your pots

If you don’t glaze carefully and follow instructions you could have disasterous results. The glaze ran off these pots and they stuck to the kiln shelves. I had to remove them with a hammer and chisel, like in the photos below.

Please do not use runny glazes on the outside of pots. The glaze runs off the pots and onto the kiln shelves. See the pictures above. The pots are ruined and the kiln shelves get damaged. The kiln shelves are very expensive. Shelves cost $315 each, and there are 65 of them in the kiln.

If I see a runny glaze on the outside of your pot, I will not fire it. Runny glazes are marked on the bucket lids and also on the shelf where the samples are. Runny glass many be used on the inside of pots and the lips of tall pots. They may not be used on the lips of short pots and the bottom half of any pot. Ask for help if you need it.

What is glaze?

Basically, glazes are ground up rocks containing various minerals plus clay and water. Glazes melt when fired to maturity and form a coating of glass on the surface of the pot. Glazes contain lots of silica, which is the main glass former. As the glazes slowly melt, they bubble and boil like thick syrup. As they get hotter and hotter, the glazes become more and more fluid, first to the consistency of honey and then beyond. We turn off the kiln when the glazes are mature (fully melted). If I were to accidentally over-fire the kiln, the glaze would get too fluid and run off your pots. Eventually even the pots would melt into a puddle. Glazes are similar to clays in their chemical composition. Both contain mostly alumina and silica. But glazes have more fluxes. A flux is something that causes things to melt at a lower temperature. The fluxes in glazes are elements like calcium, sodium, and potassium and are sourced from materials like lime, feldspar and talc. They flux the alumina and silica in the glazes and cause the glaze to melt into a glass and fuse to the pot’s surface. Colors come form metallic oxides, like red iron oxide, copper carbonate, cobalt carbonate, rutile and titanium dioxide, which we add to certain glaze. The hot, melted glaze fuses to the clay. Chemical reactions take place. The heat, atmosphere in the kiln, metallic oxides and other glaze materials all affect the color and look of the fired glaze. We fire our pots in a reducing atmosphere.

Why are some glazes runny?

When fired to maturity, some glazes are inherently more fluid (runny) than others. We use many glazes. Some are runny, some are not, some are in-between. When application of the glaze is thick, glazes are more likely to run. When glazes are applied unevenly, resulting in thick and thin spots, the thick spots will be more likely to run. When glazes are overlapped, they are more likely to run. Some glaze combinations become extremely fluid where they overlap, even though those same glazes, when used by themselves, may not be runny. This is known as a eutectic. Example: the overlap/combination of our Chun and Titanium glazes form a eutectic and become very runny.

The heat is Awesome

EVEN THE POTS CAN MELT

There are different kinds of clay. The have different properties, like color, temperature range, plasticity, and absorbency. We use Groleg porcelain. It is white, strong, high fire and non-absorbent when fired.

Don’t ever bring in clay you got somewhere else. We fire only Fireborn porcelain, so we know it is safe in our kiln.

I had a similar issue once when someone brought in a little pot he made in Africa. It was small, but made a big, expensive mess. He didn’t think to tell me it was not Fireborn’s clay.

Glazing independently

Glazing can make or break your pot. A mediocre pot can look great with a good glaze job. A great pot can be totally trashed by a poor glaze job. It takes time to learn how each different glaze behaves and how they react with one another. Maintain a journal.

Poor glazing damages kiln shelves and costs money. I may need to disassemble the stack to clean the shelves. I may need to replace the shelves, and these shelves cost $315 each. There are $18,000 worth of shelves in the kiln.

BEGINNERS

You are a beginner unless otherwise designated. Beginners may not glaze without close supervision. If you wish to glaze independently consult your instructor and ask him/her to add you to the list.

SUPERVISION MEANS

- You have to have your glaze plan FOR EACH POT approved by your instructor or a mentor.

- After glazing, your pots must be inspected and approved BEFORE you put them on the shelves.

- An independent glazer, mentor or instructor MUST be in the glaze room with you when you glaze.

- You may not dip in the buckets labeled “DANGER”, i.e.Copper Red, Oil Spot, and Titanium etc. They are too runny and require more experience. You may use Copper Red, Oil Spot and Titanium squirt bottles to apply glaze to the inside of your pots. That is safe because the glaze can’t run off your pots and onto the shelves.

- You will remain in the beginner category until certified otherwise by an instructor.This will probably take A FULL YEAR to accomplish. If you feel you’re are ready to glaze independently discuss it with your instructors.

INDEPENDENT

There is a list of independent glazers posted on a clipboard in the glaze room. They may glaze independently. If you run glaze onto the shelves or do “crazy glazing,” you will be moved back to the beginner category.

MENTOR

Mentors are experts who are able and willing to help others. See the list.

throwing Skills

I want you to more than succeed. I want you to excel. There is a wealth of information on my website and links to hundreds of other pages, each of which contains even more links. So please explore this page and a few of the links on the bottom to get you going.

Here are some tips. It is normal for beginners to have trouble keeping their pots on-center. With each new pot, see if you can get a little farther along before the pot gets off center.

- Centered pots are easier to throw and trim than off-center pots.

- If you plan to trim a pot, be sure the lip is level. Cut the lip off with your needle tool to level it if you need to.

- Off-center pots can be beautiful, but you will have to trim them on the wheel when you first make them to get them down to a decent weight.

- The clay must be adequately wedged. It there are lumps or air bubbles in the clay it is hard to center. Even if you do manage to get it centered – as soon as you stick your thumb into the clay to open it up, you displace the lumps and bubbles and the clay gets off center again.

- The clay must be adequately lubricated. If the clay gets dry, it twists and wrinkles. That happens because of the friction and drag caused by your hands sticking to the spinning clay. Conversely, too much water is a waste and a detriment. It fills up the splash pan and makes your pot too soggy and weak.

- The wheel sbould be spinning before you put your hands on the clay. First, lubricate the clay, then apply gentle pressure and then use more force. When you let go of the clay – do it gradually, as the wheel spins, to keep your pot on center.

- Don’t make jerky movements or twitch. Any sudden movements of your hands or changes in the wheel speed can throw the pot off-center.

- Avoid thin spots in the wall of your pot. Keep your finger pressure steady and the gap between your fingers even as you pull up the clay.

- Work small first. If you can’t execute a technique or form with two pounds of clay, you won’t be successful with 3 pounds.

- Make your throwing lines close together. They should be about 1/8 of an inch apart.

Making good pots: Use adequate lubrication, i.e., water, but remember to empty the splash pan before it overflows. First spin the clay, then touch the clay gently, slowly applying more pressure. Don’t twitch or jerk your hands, use steady pressure. Don’t goose the foot pedal either. Sudden changes in wheel speed jerk the pot off-center. When pulling up, throwing lines should be close together. To achieve this, pull up slowly relative to the speed the wheel is turning. The slower the wheel is spinning, the slower you should ascend. Slow the wheel speed as you ascend and your fingers get close to the top of the pot. Also, slow the wheel speed when you work on wide or delicate forms. Don’t make the lips too thin and wimpy.

Making better pots: Work quickly. Maximum of 15 minutes per pot. Make the pot grow with each pull. Don’t waste time on off-center pots. Trash the pot as soon as it gets off center. Keep the walls uniform in thickness. Never create a thin spot in the middle. Weigh your clay. Begin with 2 pounds of clay. When you can make a good 2 pound pot, try using 3 pounds and making larger versions. Practice making tall cylinders. Don’t save them, practice making them taller and thinner!

How to make beautiful pots: Master the above. Look at pots in galleries and books. Sketch the forms you like. Use tracing paper for symmetry. Bring your sketchbook to class and use it! Use ribs when you throw to get clean, flowing curves. Give yourself the authority to be bold and decisive. Wimpy is always bad! Work in sets. Make 5 similar things. Evaluate and discard the weak forms and pots. Come to class with a plan. Know what forms you want to work on. Ask for help when you need it.

Product design

When you, as a potter, create something, you are doing product design. Reviews of products abound on the internet. “Which potato peeler is best?” “Does the ergonomic grip really work?”

Once you have the skill to execute a plan, you are designing. You won’t be able to fully evaluate and appreciate your work until you use it at home. Maybe it doesn’t fit the intended purpose, but it may serve other functions. It may become a loved and frequently used item; maybe it will wind up in the basement.

Think about your design and don’t quit after the first attempt. Your pottery will evolve as you thoughtfully critique it. It takes time and persistence to make a good pot. Throw six variations of the same item, evaluate them as you throw. Line them up. Look closely. What makes some better than others? Maybe discard a few? Take notes on weight and wet dimensions. When fired, are they too small, too big, clumsy, whatever…. By this time a month has passed since you threw them, so those notes really come in handy when you go back to the wheel and make more.

Throwing Exercises

- Using the same amount of clay each time, see how tall a cylinder you can throw.

- Cut each one open to observe the thickness and evenness of the wall.

- Throw a round form for a teapot base.

- Throw a tall thin bottle form.

- Throw a tall bowl.

- Throw a wide shallow bowl.

- Throw a plate.

- Throw a baking/spoufle dish with a flat bottom and straight sides.

- Throw a mug.

- Throw a honeypot or small casserole with a lip flange and lid.

- Throw a teapot spout.

- Make an assortment of lid styles.

- Make a fat pot that necks in at the top.

- Alter each of the above forms while it is still on the wheel.

- Observe pots and try to analyze what makes them good or bad.

- Think in anatomical parts, i.e. lip, neck, shoulder, belly, foot.

- Think emotionally: is it sensual, open, friendly, curious, whimsical, or distressed?

Form, color and Decoration

- Do they all work together?

- Does it look light, heavy, ethereal or clumsy?

- Where is the visual center of weight?

- Where is the physical center (top to bottom)

- How far up the pot are the skinniest and fattest parts?

- Where do the lines take your eyes?

- Look at the “S” curves.

- What is the relation of the width of the foot to the neck and lip?

- Are any parts exaggerated, and if so, is this an asset?

- Is there a sense of movement?

- Is there a sense of balance?

- Is there a sense of tension?

- Is it purely decorative?

- Is it truly functional?

- Is the golden mean used?

- Pots with handles, spouts or other additions are more complex.

- Do all the parts work together functionally and aesthetically?

- How do all of the above relate to one another?

- Sketch some pots. Use tracing paper. Draw only the right side. Fold and trace the left to make it symmetrical. Analyze it.

- I find “The Golden Mean” very useful in developing classical forms with pleasing proportions. Look up Golden Mean on the web.

MORE THROWING VIDEOS

In addition to the videos that I made, I suggest you check out this other person’s videos on basic throwing too.

For more advanced throwing help I suggest this page.

Advanced throwing exercises

This is a collection of videos by other potters I thought you might find useful. Especially the first two on making handles. My favorite on pulling handles is Tom Coleman’s. It is almost exactly what the way I make handles, and he uses a lot of the same vocabulary as I do.